Combining immunotherapies to tackle treatment resistance in lymphoma: The RiVa Trial

This early-phase clinical trial is testing a ground breaking new method of treatment for lymphoma (cancer of the lymph glands) that could potentially change the way we treat this disease. RiVa is a trial that has been entirely conceived in Southampton, from bench to patient in just two-and-a-half years. The great majority of drugs take an average of ~12 years to enter the clinic. RiVa is looking into a new combination of two drugs to treat lymphoma – rituximab, which targets CD20-expressing cells (e.g. lymphoma cells), and varlilumab, which enhances the immune system’s anticancer activity by targeting CD27 (a marker on T cells).

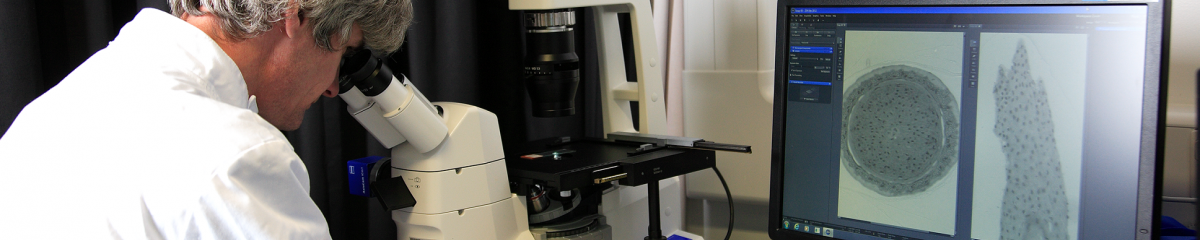

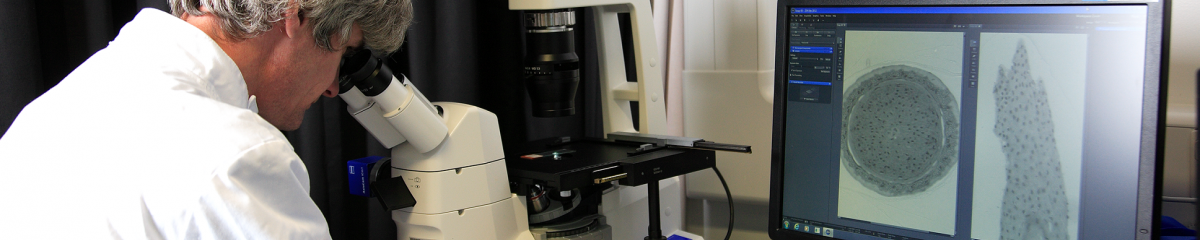

This trial’s primary endpoints are safety and response rates, but it also incorporates a comprehensive translational plan. In general, it involves the collection of sequential tumour biopsies before and after treatment to allow analysis of protein markers (using multicolour flow cytometry) and gene expression (using next generation RNA sequencing). These experimental plans will be vital in helping us to determine the biomarkers that can tease out responders from non-responders. Further, in non-responders, it will also help us to elucidate the reasons for a lack of response and how we might overcome this. The majority of the analysis is being performed centrally at the Southampton ECMC, WISH Laboratory.

The trial, funded by Cancer Research UK and the Celldex Therapeutics (NJ, USA) is being managed by the Cancer Research UK Southampton Clinical Trials Unit and run in three ECMC centres in the UK: Southampton, Oxford and Manchester; as well as at Derriford Hospital, Plymouth. The trial is being conducted on patients who have relapsed or refractory lymphoma. The RiVa trial in collaboration with the School of Cancer Sciences, Centre of Cancer Immunology, ECMC WISH Lab, Faculty of Medicine and sponsored by University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

“In this small trial, some people responded to the combination treatment and some did not, as one would expect from any study,” says Dr Lim, Antibody & Vaccine Group, Centre for Cancer Immunology, Southampton.

“But what is really interesting is that we have found clues as to what the varlilumab is doing in the tumours, helping us to better understand why there is a response in some patients and not in others.”

Varlilumab is a CD27 agonist. This means it binds to the CD27 receptor on T cells and stimulates a pathway that leads to more T cells being produced and the release of chemicals which activate another type of immune cell called macrophages. These macrophages are able to destroy the cancerous B cells that have been marked by the rituximab.

“With RiVa, we took needle biopsies of the tumours from patients who only had rituximab versus those who had the combination of rituximab and varlilumab,” continues Dr Lim.

“What we saw in those who also had varlilumab was an increase in activated T cells and evidence of activated macrophages. This data gives us confidence that varlilumab is stimulating the immune system.”

“But when we looked at the patients who responded to the combination treatment, versus those who did not, we found that the responders had a greater increase in the number of T cells, and a ‘hotter’ immune environment, so more expression of the genes that lead to an immune response.”

“This suggests that the patients who are going to respond to T cell stimulation are probably the ones with a more active immune environment. We don’t have a means to pick these people out yet, but we are another step along the way.”

“Our next steps are to look for a better agonist. We see that varlilumab is stimulating the immune pathways, but it’s a weak agonist. My lab is now looking at how we can engineer antibodies to optimally. We are also looking at other immune-stimulatory antibodies, beyond CD27.”